How do clothing repair shops in Buenos Aires City foster a sense of community ?

To answer the previous question, I made a short documentary about Buenos Aires' clothing repair shops, exploring how these humble establishments foster community bonds and promote sustainable behaviours. This journey began with a fundamental question: How do these repair shops contribute to community cohesion and responsible consumer practices?

Surprisingly, existing literature on Argentine repair shops was scarce, but I drew from broader studies on mending and the circular economy to provide context. I delved into Levinas's ethics of 'the other' and Heidegger's concept of Dasein, applying these philosophical lenses to understand the social dynamics of these repair spaces.

Economically, Argentina's fashion industry has weathered significant challenges, from historical periods of growth to more recent crises. The impact of global trade dynamics, especially with China's dominance (United Nations, 2017), has shaped the local market and influenced consumer behaviours. My research underscores the importance of government regulation to support local production and ethical practices within the industry, particularly in the face of these challenges.

My documentary, a labour of love during this research, captured the essence of these repair shops in Buenos Aires. It highlighted their resilience amid economic turmoil and showcased their role in fostering a sense of belonging to the citizens and promoting a social and sustainable space for Buenos Aires city. Through interviews and observation, the documentary revealed how these shops go beyond mere repairs; they cultivate a sense of community and ethical consumption habits.

Barty's clothing repair shop

Collier (1967), a pioneer regarding visual research argues in his book “Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method”, the importance of visual information as a way of collecting data when studying cultures as it covers social aspects of a community that hardly could be described with written descriptions.

The visual research of this project is integrated with photographs and a short-documentary film as an outcome of five in person interviews and shooting of the studied clothing repair shop environments. Each participant of the film has received consent forms both in english and spanish, to read carefully and sign in case of agreement. In addition, theproject was explained to them verbally. Visual ethnography aims to authentically commu- nicate the participant’s way of being (Pink, p11, 2001); whether individuals choose to reveal their faces in the short film is neither positive nor negative. What is most significant is the participants’ comfort through them guiding the interview process according to their preferences.

Tamy's clothing repair shop

“As participant observers we can learn the culture or subculture of the people we are studying. We can come to interpret the world more or less in the same way that they do. In short, we not only can but also must learn to understand people’s behaviour in a different way from that in which natural scientists set about understanding the behaviour of physical phenomena.” (Atkinson, 2007, p.8)

Carmen's clothing repair shop

In contrast to the previous quote, which describes the point of view about the results that could be obtained from an ethnography (Atkinson, 2007), this research has opted for a levinasean approach. The previously ana- lysed author, Levinas (1969), affirmed in his book Totality and Infinity that the action of the attempt to understand the other would preclude the existence of the other in its natural essence of being and be counterproductive.

He justifies the impossibility of understanding the other due to the logical reason of not having gone through identical experiences. In agreement with Levinas, the research methodologies will follow the mentioned approach without confirming any understanding and profoundly analysing the clothing repair shops in their natural environment, providing material that supports the seeking of visualisation and recognition of the shops.

Natalio's clothing repair shop

The short film is still a work in progress regarding its concrete meaning, as this depends on the perception and interpretation of the audience. Metz (1977) explains the book The Imaginary Signifier, which stud- ies the connection between cinema and the spectators through Freudian psychoanalysis in different ways within the book; it focuses on the distance between the film topic and the viewer. The author refers to distance as an object of knowledge, a space for ques- tioning and desire, and a “passion for the imaginary” (Metz, 1977, p.79).

Neither the visual ethnography about the film nor the dissertation seeks a complete understanding of the topic of study but an exploration, questioning and reflection, a perspective that can be observed within the outcome.

However, in contrast to Metz’s (1977) theory of film, Levinas’s (1969) concept of the other, the short film documentary does not agree in the sense of identification as powerful but otherwise, the sense of acceptance of the difference and non-self centred perspective as a potent characteristic of the protagonist of the film. Therefore, the outcome as a visual ethnography is shown and explained by others, in this case, the clothing repair shop owners, their clients and Buenos Aires city.

Tamara & Estrella's clothing repair shop

According to Hegel (1977), recognition is vital for self-esteem, Buenos Aires City (Of Repair) is an observational and participatory short-documentary that contributes to the clothing repair shop owners recognition but at the same time, the space that has given from the owner for the film to be make brought a mutual recognition to the practice area of the project.

Clothing repair shops in Buenos Aires City reflect on their workplace as a second house and welcome the citizens to save their clothing and share a moment together. These shops and their owners are practically manifesting the Dasein, being in the world (Heidegger, 1962), and this is what fosters a sense of community and contributes to foster sustainable behaviours among other individuals in Buenos Aires City.

There are 247 clothing repair shops in Buenos Aires City, according to Google Maps (2023). Despite the economic crisis, Argen- tina is suffering at the moment, the longevity of clothing repair shops in the city is between 10 and 30 years old, according to the ques- tionnaire done for this dissertation. This fact could be considered a success for these shops that went through massive economic crises such as the one in 2001.

The shops are distributed within 47 of 48 neighbourhoods. The neighbourhood called Puerto Madero, which does not have any clothing repair shops, is still being developed and has the smallest number of citizens currently living in the area compared to the other neighbourhoods, according to the official website of the government of Buenos Aires (no date). Nevertheless, as shown in figure 4.2.1, there are an amount of 9 Cloth- ing Repair shops in neighbourhoods nearby that area such as San Telmo and Monserrat, that allow citizens from this neighbourhood to also repair their clothing in an estimated between 10 and 20 minutes walk, according to Google Maps (2023).

According to the book ‘People Make Places: Growing the Public Life of Cities’: “Cities were invented to facilitate exchange of ideas, friendships, material goods and skills. How good a city is at facilitating the exchange process, providing platforms for everyday interaction and information flows the basis and content for the public life of cities.” (Mean & Tims, 2005, p.9).

Clothing Repair Shops are locations accessible in every neighbourhood of the city, which contributes to and increases the possibility of people accessing to repair their clothing and to have a space for also exchanging ideas and creating friendships, which will be profound within this chapter through a small survey done to 20 shop’s owners.

Table 1, J. Gayon, 2023.

Visualisation the longevity of the Clothing Repair Shops Google Sheets (2023).

As Table 1 demonstrates, the majority of the shops, %31,6, which would be six shops, are between seven and ten years old. In contrast, the second majority, an amount of the five shops, are between four and six years old, demonstrating their resilience to the following critical moments the country was through, such as the economic crisis of 2001, the pandemic and the imports open to China in 2011. The permanence of the rest of the shops varies; three are between fifteen and 21 years old, two are between one and two years old, one is 12 years old, and the oldest two are 30 years old.

The resilience of these shops is extremely valuable for the future and present of fashion. Apart from their social influence regarding social values, they save a considerable amount of clothing that otherwise might be wasted.

As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, globally, customers lose approximately USD 460 billion in value each year by discarding clothing that could still be worn. Additionally, some garments are estimated to be discard- ed after only seven to ten uses (Ellen Macarthur Foundation, 2022).

Within the survey, the next question is, ‘Approximately how many garments are fixed per month in the shop?’.

Table 2, J. Gayon, 2023.

Visualisation the amount of garments each shop repair per month. Google Sheets (2023).

As seen in Table 2, the amount of garments repaired differs for almost every shop except for five that repair an estimated forty and forty-five garments and the other two that repair sixty garments every 30 days. Never- theless, 20 clothing repair shops located in Buenos Aires city repair a minimum amount of 2270 and a maximum of 2305 garments per month, which, within a year, would result in between 27240 and 27660—a number that could be expected to grow due to the number of new clients the shops have.

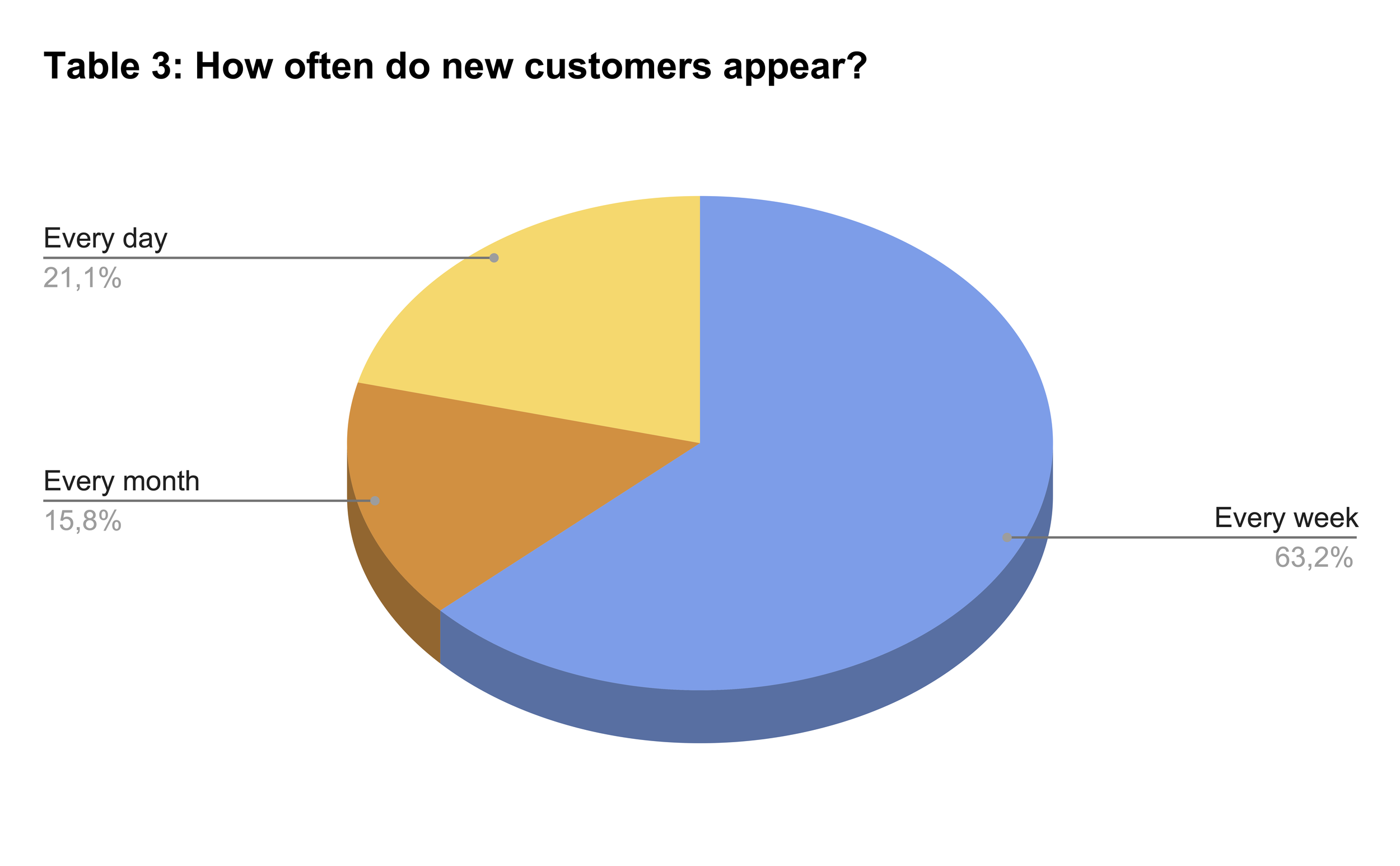

As shown in Table 3, %63,2 of the clothing repair shop owners affirmed that they have new clients every week, while %21,1 report- ed having new customers every day and %15,8 every month.

The increase in clients could be interpreted as citizens engaging more with sustainable practice. Nevertheless, it could be possible that they have to get their garments repaired more often because they are considerably less durable than in the past. (Johnson, 2023).

Table 3, J. Gayon, 2023.

Visualisation the amount of garments each shop repair per month. Google Sheets (2023).

Nevertheless, the significance of these shops for the community of Buenos Aires citizens does not only rely on clothing repair. All the owners have answers that after the first time (Table 4), a percentage between %80 and 100% of the clients return.

Table 4, J. Gayon, 2023.

Visualisation of the percentage of clients that return after the first time they visit the shop. Google Sheets (2023).

This pattern could reflect a positive encoun- ter between the clients and the owners due to the high percentage of citizens that come back.

Returning to the concept of Dasein, this survey’s question provides a better explanation of the contribution of the sub-chapter Rec- ognition, Dasein & Besorgen. Face-to-face situations are meaningful when engaging in terms of Dasein, being in the world (Heidegger, 1962). Hence, this question starts making visible a sense of recognition from the clients and also from the owners who remember them.

The survey’s findings (Table 5), where repair shops mention an estimated percentage of clients they also consider friends, suggest the profound and significant role of the shops aligning with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1943).

Of 19 clothing repair shops, 1 of them considers %99 of their clients as friends, while 5 consider %90 of the customers and another one %80. Apart from those, one considers %70 of their clients as friends, 4% think more than half the clients are friends, and one shop owner feels a friendship with only %10 of the clients.

As reflected in Table 5, the connections between the clients and owners transcend the practice of repairing, leading to a fulfilment of social and esteem needs, which, according to Maslow (1943), is fundamental when building personal values such as sustainability and ethics, vital needed characteristics when thinking about fashion futures.

Table 5, J. Gayon, 2023.

Visualisation of the percentage of clients that establish friendships with the repair shop owners.

Google Sheets (2023).

In conclusion, the repair shop owners’ pro- found engagement with their clients and workplace could be a clear and practical example of Heidegger’s (1962) concept of Dasein. Their approach to customers and the shops represent a phenomenological perspective (Husserl, 1983)—an experience. In this case, with a profound sense of belonging, as evidenced by their connection to their workplace, described as a second home in 100% of the cases.

This collective human existence, rather than self-centred, defines their human experience, revealing its meaning and depth through its interconnectedness with the surroundings. Heidegger’s (1962) “Being and Time” is a valuable tool for contemplating human existence, emphasising the significance of including external influences as integral aspects of one’s self. The repair shop owners’ homes indicates a deep connection. It illustrates a sense of belonging that could be considered decisive for self-realisation and personal growth—crucial considerations when reflecting on sustainability (Maslow, 1943).

Bibliography

Atkinson, P. (2007) Ethnography: Principles in Practice. London: Routledge.

Hegel, G.W. F. (1977) Phenomenology of Spirit. Oxford, New York, Tornado & Melbourne: OX- FORD UNIVERSITY PRESS. Available at: http://www.faculty.umb.edu/gary_zabel/Courses/Marx-ist_Philosophy/Hegel_and_Feuerbach_files/Hegel-Phenomenology-of-Spirit.pdf (Accessed: 31 Aug 2023)

Heidegger, M. (1962) Being and time. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell.

Large, W. (2015) Levinas: Totality and Infinity. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Metz, C. (1977) The Imaginary Signifier. Bloomington: INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS.

United Nations. (2017) Territorio, infraestructura y economia en la Argentina. Available at: http://nulan.mdp.edu.ar/2753/1/completo-textil-2017.pdf (Accessed: 25 Aug 2023)